The Start Of The Siege Of Baler

by Jose Maria A. Cariño

War was declared between Spain and the United States on 1 April 1898. On 1 May, the U.S. naval forces took over Cavite and destroyed the Spanish Armada. In history, the Americans call this event the Battle of Manila, while the Spaniards call it their defeat in the Battle of Cavite. Technically it is correct to call it the Battle of Cavite as the fire fight really occurred off the coast of Cavite. For dramatic effect the Americans, being early practitioners of the principle of sound bite, thought to name the event 'after the capital of the Philippines rather than the obscure Cavite, of which the American public had never heard. A few days before the battle, the Spanish authorities thought it wise to create the Philippine Militias, using native soldiers, hoping that these would help their defense against the Americans. Guns and bullets were issued to these newly formed troops. The Filipinos used these same weapons against the Spaniards and later on against the Americans when they realized that they had been sold down the river.

Before the end of June 1898, Teodorico Luna y N ovicio received three communications from General Emilio Aguinaldo instructing him to attack and take over all the Spanish detachments or civil authorities in the Distrito del Principe. Aguinaldo knew that since there were only a little over 50 soldiers in Baler, taking over the detachment would not prove difficult. A victory in Baler would serve as symbol and encouragement for the Katipunan troops. Teodorico demurred at these orders as it coincided with the time to harvest the rice in the fields. Teodorico also hesitated over the fact that the soldiers who had arrived in Baler as reinforcements were better trained than his own newly recruited men. Those soldiers had battle experience, fully armed, and were well stocked with ammunitions. However, knowing that Aguinaldo's wrath would be upon him if he disobeyed, he rushed to Pantabangan to pick up the measly 15 firearms allotted to his group by the Katipuneros.

While it seemed that the siege was the story of a small army's resistance to 337 days' worth of harassment and superior firepower, the truth was that at the start of the siege the Katipuneros under the command ofTeodorico Luna did not have the kind of firepower, trained soldiers, and superior forces that would have enabled them to overrun the church in a short period of time.

Luna arrived in Baler in the afternoon of26 June and immediately ordered all town inhabitants to abandon their houses that night and bring with them their valuables save for furniture and other large objects that would arose the suspicion of the Spanish soldiers. Luna's strategy had two objectives: that the civilian population of the town of Baler would not suffer any untoward incidents during the siege or as an effect of the crossfire, and that his own soldiers and their operations would not be hampered by curious kibitzers.

The Franciscan parish priest Father Candido Gomez Carreno however must have suspected that something was amiss because instead of sleeping that night at the convent or the parochial house, he slept at the Comandancia. It was possible that he had been forewarned by one of his devout and faithful parishioners. When he woke up the next morning, 27 June, he went back to his convent and found out that the servants had all disappeared together with a chest of the dirty clothes that the soldiers had sent for washing and 340 pesos from the coffers of the church. The priest rushed to the Comandancia to report the event to Captain Enrique de las Morenas. It was then when they realized that the town had been abandoned by its inhabitants in preparation for the forthcoming attack of the Katipuneros.

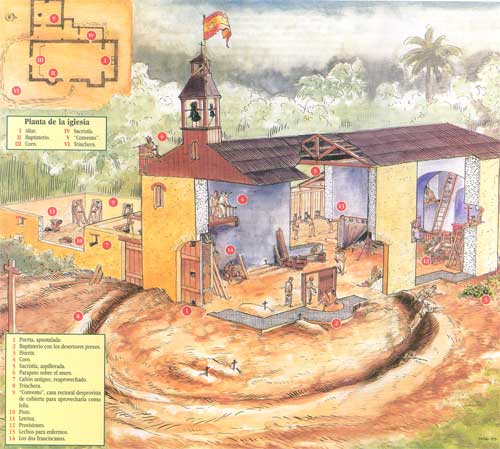

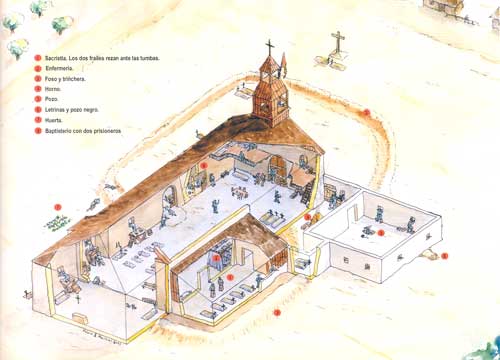

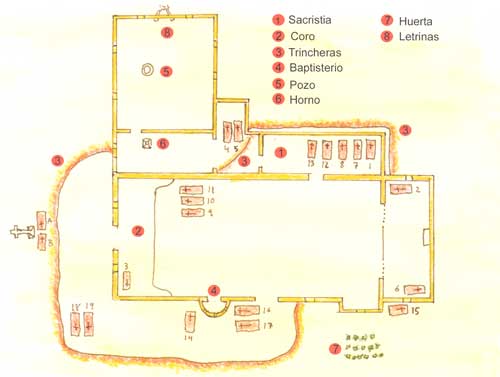

Preparations For The Siege

The soldiers in Baler knew that the Spanish navy had been beaten by the American forces in the waters of Manila Bay. The also knew that the Katipuneros were taking over many of the Spanish detachments in the nearby provinces. They were also aware that they were incommunicado and their letters to the detachment in San Isidro, Nueva Ecija, never reached their destination as these intercepted by the Filipino revolutionaries. They however had brought in some provisions when they landed in Baler in the cruiser Don Juan de Austria.

They supplemented their supplies by collecting money from the town inhabitants. Captain Enrique de las Morenas increased revenues by collecting taxes and issuing cedulas, office taxes, and other forms of taxation. To implement this, the captain hired the town teacher Lucio Quezon as his adviser. He also ordered the tilling of the terrains of the Comandancia to increase the food supply of the detachment. He assigned Maestro Lucio in charge of the farm as a reward for siding with the Spaniards during the first revolt of Baler. The captain assigned the task of tilling the farm to the natives who could not pay their taxes and so had to serve the so-called polo y servicio or the forced rendering of services in public work projects such as road maintenance, digging ditches, cleaning public buildings and roads. This made the townsfolk hate the captain as this task of tilling the land did not fall under any of the categories of public works. It also made the town inhabitants distrust Maestro Lucio whom the captain appointed to coordinate the running of the farm. It led to the murder of Maestro Lucio by some of the Baler townsfolk, leaving the 19-year- old future president of the Philippines Manuel Quezon, born 19 August 1878, fatherless a few weeks before the Siege of Baler. This distrust may have been extended to Manuel Quezon's mother, Maria Dolores Molina, which led to the rumors that she took refuge in the church together with the soldiers during the siege. There was no proof that she was inside the church during the siege. It could not be denied however that during the siege, some Baler residents, including Maria Dolores Molina, out of Christian charity, took pity on the Spaniards inside the church and helped them in some form or another, otherwise they would not have survived such a long siege. It would then be logical that the ones assigned to bring food or any form of aid would be the women. Proof of this is that among the photographs taken of the soldiers after the surrender, a lone Filipino woman sits among them. She may have been one of those that provided help to the besieged soldiers and including her in the picture was an expression of the soldiers' gratitude for her help.